Atlantropa: The Ambitious Idea of Uniting Europe and Africa by Draining the Mediterranean

Share

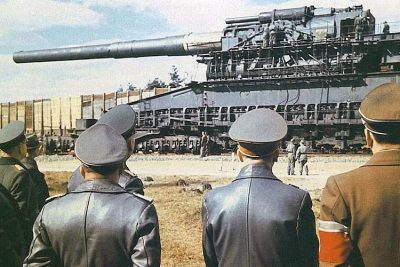

An artistic impression of how Atlantropa might have looked. (Ittiz / Wikimedia Commons)

Every one of us inspires a variety of ideas during our lifespan, alas very few of us have ideas that would be considered revolutionary. Even less, revolutionary ideas in terms of helping the world on a grand scale. This can be an ambiguous line of thinking of course because some ideas are idolised by some, and criticised by others. One which exemplifies this wonderfully is the brainchild of Bavarian-born Germany architect Herman Sörgel. His plan was to create a zone called Atlantropa by draining the Mediterranean Sea. It would link Europe and Africa into a supercontinent.

The Atlantropa project

Herman Sörgel. (Süddeutsche Sonntagspost)

Herman Sörgel was born in Regensburg, within the forest region of Bavaria, Germany in the year 1885. Many of his family were architects so the seed was already planted for a life of orchestrating grand designs. But, not even his parents would have envisioned that their child would devise something as grandiose as this. After studying at the Technical University of Munich for four years he was ready to unleash his titanic scheme.

Atlantropa certainly sounds more outlandish now than it did at the time of conception. The reason for this is that Europe was naturally in dire straits after World War One and so the architect looked for a way to ease this by creating more land. That was the main point of wanting to drain the Mediterranean; It would make available over half a million square kilometers of land (576,000 Km2 to be precise and 1/5 of the total landmass in the Med.) Far from an easy process, this would take approximately 150 years to complete.

Sörgel’s Dams were to be positioned at various points of the Mediterranean Sea. The primary dam and power station would be across the Strait of Gibraltar in the south of Spain. The second would be the distance between Sicily and Tunisia to lower the water level. Finally, the third would be on the Sea of Marmara – a hydroelectric dam – separating Turkey and Greece. Other alterations would be an extension of the Suez Canal which would connect Venice to the sea.

Benefits of Atlantropa

Sörgel and those impressed by the plan spoke of the plentiful benefits of Atlantropa. A major incentive being the amount of hydroelectric energy said dams would produce. This type of power was fairly unknown at the time with fossil fuels dominating and nuclear power blossoming as a newer and more trusted idea. Yet, these days we can see the potential of kinetic energy through hydroelectric power.

With the sea levels lowered it would unearth vast swaths of new land, much of which would be implemented into farmland. In turn, the basin of Lake Chad would increase, meaning the Sahara desert would be irrigated, bringing much needed clean water to the region. Also, shipping routes to and through the basin would make Sub-Saharan Africa more accessible and open up migration routes for those needing to travel. And of course, the scale of the project would open up thousands of new jobs for a century and a half at least.

An evocative and seemingly just prospect of the dam system was for it to be administered by an independent, nation-less body. While the main solution behind it was to improve the economic situation after the Great War by creating land and energy it also looked to stem any future wars in Europe. Sörgel recommended that the body of power in charge would cut off any hydroelectric power to a country (based on the Mediterranean) that looked to start a new war. A shrewd punishment.

Reception

The reason that the plan also known as Panropa received and retains any sort of credence is that Herman Sörgel dedicated his whole life to glorifying the idea. His first book was written in 1929 and the architect was far from coy with the title, The Panropa Project, Lowering the Mediterranean, Irrigating the Sahara. It would later be changed to Atlantropa once more of the public become aware of the enterprise. The German architect-come-writer would eventually pen a total of four books to defend his revelation while presenting thousands of articles and lectures culminating in a multitude of followers. There is even an archive in Munich devoted to his work, at the Deutsches Museum.

Death of an idea?

Following the First World War and the Weimar Republic, the NAZI party took power. As heads of the country, they were shown the plan of Atlantropa but were not interested in pursuing the idea further. If the scale alone did not disparage them then one of the goals of the Nazi regime – a European German Empire or Lebensraum – certainly did.

The same was to be said for the Allied Powers including Britain, France and Russia. There were many reasons for this, one of which is that nuclear power became prominent in Europe and negated the need for the supposedly less powerful hydroelectrical energy.

Although the Atlantropa Institute – a society created and maintained with the supporters of Sörgel’s work – existed until 1960, Herman Sörgel met his end in 1952. A tragic finale would come to the visionary and while some would say he could see into the future he could not foresee a road accident before his 68th birthday. While cycling to a lecture in Munich an anonymous car struck him. With it being on a straight road and no drivers admitting to the accident some have claimed it to be a conspiracy to murder.

Effectiveness

With many of the problems in Europe and Africa increasing as the population of the world rises Atlantropa seems an idea that would relieve many of these issues. That is from the forefront however and looking beyond the surface, many more problems would surely arise because of the nature and sheer scale of the project. This is perhaps through a mortal’s eyes and maybe a mastermind such as Herman Sörgelhad solutions for any given circumstance. To promote such an idea he must have believed that his invention would cure more evils than not after all.

With the trouble in the Middle-East in recent times, this would be an example to hypothetically or theoretically test the proposal. Mass migrations from the Levant to Europe would certainly be helped in a system like this in terms of access. At the same time, there are those who believe that free-roaming migrations such as these are not beneficial especially in the current climate.

Atlantropa began as an ambiguous project in terms of whether a good idea or not and will continue like that forever more it looks. It is hard for many people to grasp the pros and cons of such a massive undertaking, especially within a constantly changing world. It really depends on a person’s thoughts politically and socioeconomically if Atlantropa would help or hinder Africa and Europe. In terms of supplying power and water to both continents, it would definitely have benefits but the potential katzenjammers are endless…

Enjoyed this article? Also, check out “Rejected for Paris, Project Plan Voisin is Accepted Part of World Architecture“.

Recommended Visit:

Deutsches Museum | Munich, Germany

Fact Analysis:

STSTW Media strives to deliver accurate information through careful research. However, things can go wrong. If you find the above article inaccurate or biased, please let us know at [email protected]