The Great Fire of London: The Blaze That Destroyed 80% of England’s Capital

Share

A lithographic print of the great fire of London. (Museum of London)

The infamous Black Death or Bubonic Plague of 1346 transformed the social outlook in England so much that by 1665 more and more people inhabited towns and cities, fueled by the industrial revolution sweeping their nations. When another strain of the plague – the Great Plague – struck London in 1665 it did not kill the millions that the plague of 1346 did due to advances in medicine and hygiene, but estimates conclude that at least 100,000 Londoners perished from the disease. Another tragedy would strike only a year later. The Great Fire of London ravaged the city, feeding on vastly wooden constructs which acted as a tinderbox of destruction within a panicking city. A country at war with the Dutch, the French and the Catholics, several theories and conspiracies arose on who was to blame.

Flammable abodes

Safety standards in England at that time were nowhere near as stringent as they are now. In a society so reliant on fire for industry, lighting and insulation among others, cramped wooden houses were a massive safety issue even though most fires were extinguished quickly before spreading. This was warned by many leading figures alas, there were few alternatives as cheap. These mostly residential buildings were primarily made of oak, separated by straw floors and thatched roofs. There was not much open space between buildings in most parts of the city; narrow streets meant that some roofs even touched across streets.

Sunday, 2nd September 1666

September 1666 was an especially warm, dry month. In the east of the city, near London Tower was a bakery which supplied the Royal Navy biscuits. It was located in Fish Yard, just off Pudding Lane. Shortly after midnight on the 2nd of September, the blaze started and spread quickly due to the warm weather making the wood and straw extremely dry.

Samuel Pepys. (National Portrait Gallery)

One of the best accounts of the terror came from famous writer Samuel Pepys, a Member of Parliament and British Navy administrator. His diary is one of the most famous works in English literature, totalling over 1 million words. Pepys climbed to the top of the Tower of London to which he saw his city burning. He spent much of the next week sailing on the River Thames detailing the path of the fire. The Lord Mayor Thomas Bloodworth was called to the district where the fire started. He would not allow the experience firefighters to destroy buildings in the path of the conflagration because he could not find the owners. He feared reparations from the landlords no doubt.

The fire spread with thousands of people trying to escape the vicinity including via the river Thames. Stores of oil and gunpowder on the banks of the river meant this could be perilous also, and when the blaze hit them it turned into chaos.

People lost hope of putting out the fire as gale-force winds gave oxygen to the blaze. Refugees lined the streets making it difficult for fire-fighting carriages to get through. The destruction was so intense that King Charles II sailed into the city and demanded that buildings be torn down to create a fire break.

Monday, 3rd September 1666

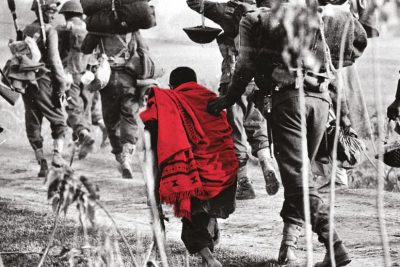

The financial district was hit on Monday, destroying the homes of bankers and the Royal Exchange – the city’s center of commerce. Paranoia and blame set in by this point and with the wind starting setting seemingly random buildings alight, foul-play was suspected. Reports came of foreigners whose nations were at war with England feeding the fire. Eyewitness accounts of grenades thrown into buildings. Many French and Dutch nationals living in England were lynched or their stores looted by the blood-hungry mob. In an effort to stop the xenophobic mobs and quench the fire, King Charles gave the command to his experienced brother the Duke of York. He took the army as well as teams of mercenaries to destroy more buildings – creating a break way. They were said to have rescued many foreigners from the mobs.

Tuesday to Sunday

These methods continued on Tuesday but it was also the day of greatest devastation raising the likes of St. Paul’s Cathedral to the ground. Decreased winds and more fire-breaks meant that finally the blaze looked set to quell. By Wednesday the majority of the damage had been done and the blaze was controlled although it took until rainfall on Sunday before the fire was extinguished and until March the following year until no embers reignited.

Model of a 17th-century fire engine. (Steven G. Johnson / Wikimedia Commons)

Illustration of the 17th-century fire engine in use. (Wikipedia Commons)

Great Fire of London: Arson or accident?

Most believe Thomas Farriner, a local baker accidentally started the blaze, or rather, his maid who cleaned the kitchen. He always denied this, stating that the embers in his bakery were safely cleared from the oven as always. Everyone in the house escaped except for the maid who was the first victim. While Thomas Farriner’s household is believed to be behind the accidental fire there have also been a number of theories, some labelled conspiracy theories for their extremity. Not only after the fire but during it did these theories come to light. The main motives being that England was at war with the Dutch and the French.

A plaque in Pudding Lane commemorating the Great Fire. (Ivory / Wikimedia Commons)

A French watchmaker actually admitted to the crime but it was later found out that he wasn’t even in London at the time. The man was considered mentally handicapped but he was hanged before he could be cleared. Nostradamus, a French soothsayer, predicted that a fire would kill many in London in the year 66.

“The blood of the just will be lacking in London,

Burnt up in the fire of ’66:

The ancient Lady will topple from her high place,

Many of the same sect will be killed.”

The Dutch had a reason for revenge also as the English navy burned a Dutch town to the ground in recent years.

More far-fetched beliefs exist such as a group called the Freemasons – a fraternal organisation–wanting to create a new city. Christopher Wren– a highly acclaimed architect -who rebuilt London was a Freemason after all. Others feel it was a strategy from those in high powers to finally rid London of the bubonic plague. The general belief in London at that period was religious of course, with God punishing Londoners for their greed. The church promoted this reasoning by highlighting that the blaze started in Pudding Lane and ended in Pye corner.

The aftermath

Whoever caused the catastrophe, the end of the destruction claimed no less than 13,000 houses. Less than ten deaths were recorded but experts believe thousands perished as the fire reached temperatures as hot as 1,250 degrees Celsius, enough to burn skeletons. Samuel Pepys described a local park called Moorfield, a site where many of the survivors had gathered (80% of London had been made homeless). It was a heartbreaking sight with swathes of suffering and now homeless people. Temporary accommodations were built but many were not adequate meaning even more would perish in the winter. 25% who left the city for new lives would never return.

This painting shows survivors with their cattle near the Old London Bridge. (Museum of London / Wikimedia Commons)

Christopher Wren was in charge of the city’s permanent restoration which provided the blueprints for the foundations of modern London including a new and improved St. Paul’s Cathedral.

If there is a silver lining to be taken from this tragedy is that although the Great Fire was a catastrophe, it did cleanse the city somewhat. A safer London would be built on the ashes and improvements to the squalor living conditions were made. The remnants of the bubonic plague were wiped out but would return – albeit in lesser numbers – in the not-too-distant future. A cure has since been found. A monument to the Great Fire of London still stands near Pudding Lane, close to where the blaze started.

Monument to the Great Fire of London. (Eluveitie / Wikimedia Commons)

While safety standards have improved considerably, a recent blaze in London (2017) killed 72 people in Grenfell Tower, West London, warning that constant precautions have to be taken when constructing and maintaining buildings. Even then, fires can still spark and spread.

Grenfell Tower fire, 14 June 2017. (Natalie Oxford / Wikimedia Commons)

For more detailed information the Telegraph has a timeline of events on the Great Fire of London.

Enjoyed this article? Also, check out “The Black Death: When Tens of Millions of Europe’s Population Was Killed by the Bubonic Plague“.

Fact Analysis:

STSTW Media strives to deliver accurate information through careful research. However, things can go wrong. If you find the above article inaccurate or biased, please let us know at [email protected]

Recommended Read:

Recommended Read:

The Ghost Map: The Story of London’s Most Terrifying Epidemic – and How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World | By Steven Johnson

Genre:

Non-fiction > History