John Stapp: The Air Force Pilot who Survived the Fastest Rocket Powered Sled

Share

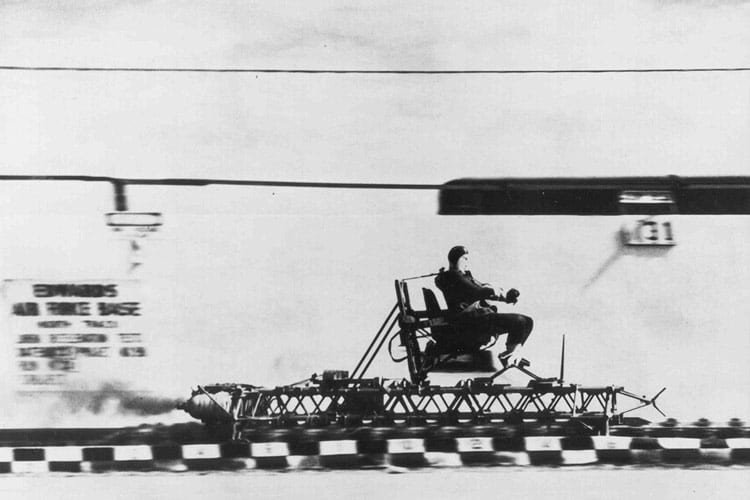

John Stapp being propelled in a rocket-powered sled at Edwards Air Force Base. (USFG / Wikimedia Commons)

Aviation technology had leapt massively in the years succeeding World War II. Thanks to the new streamlined fuselages and more powerful engines, planes had become faster and were capable of flying at much higher altitudes than previously thought. That said, scientists had little knowledge on how these advancements would affect the standard pilot. Faster and higher altitudes meant that pilots, on average, would have to bear significantly higher G-force on ejection, or on crashing. However, while others were worried about the effects, one man – John Paul Stapp – was absolutely fascinated by them.

John Stapp’s curiosity

John Stapp was born in 1910 to Reverend and Mrs. Charles F. Stapp, both of whom were American missionaries that were then stationed in Bahia, Brazil. Soon after, the family moved to Texas. This is where Stapp’s illustrious academic career began. By the age of 34, he had received his bachelor’s degree from the Baylor University, a Ph.D. from the University of Texas in Biophysics and an MD from the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities.

While interning at the Saint Mary’s hospital in Duluth, Minnesota, he decided that he wanted to join the military. On October 5, 1944, Stapp enlisted in the Army Air Corps as a doctor. By 1946, he had been allocated to the Aero Medical Laboratory at the training facility of Wright Field. This is where his curiosity for testing human tolerance really exploded.

In this respect, John Stapp was completely riveted by the ejection seat tests that were being conducted at Wright Field at the time. At the time, many renowned scientists were of the opinion that the body can only withstand a maximum of 18 Gs. However, Stapp did not concur. Testing the limits of human tolerance was to soon become the subject of one of Stapp’s immediate research projects.

Early experiments

Stapp’s first tests began in early April 1947, at a 2,000-foot long course at the Muroc (later renamed Edwards) Air Force Base. To prepare for the experiment, he had powerful rockets added to a sled, codenamed, Gee Whiz. Additionally, at the end of the course, Northrop engineers built in 45-foot long hydraulic brakes. While the rockets would help propel the sled to near crash speeds, the brakes would help create the required G-force.

Essentially, the faster the sled went, the more G-force could be produced. After experimenting with a test dummy dubbed Oscar Eightball, the team was ready to begin human tests. By June 1951, Stapp managed to conduct close to 74 runs at the track. Apart from seven other volunteers, he, himself, was one of the most frequent riders. However, Stapp was not satisfied with the results at Muroc, as it had its limitations.

File photo of John Stapp (Left). An unknown subject being prepared by Stapp and Captain Eli Beeding for a rocket test (Right). (USAF / Wikimedia Commons)

Eventually, he got the opportunity to push things further when he was transferred out of Muroc to the Holloman Air Base in New Mexico. While here, along with Northrop engineers, he built an even more powerful rocket sled. This time, the sled, codenamed Sonic Wind No. 1, was capable of producing speeds of up to 421 miles an hour, with about 27,000 pounds of thrust.

In all, when it stopped, the test subject would be exposed to close to 22 Gs – the highest ever recorded at the time. While the tests went on routinely, with every trial, Stapp tried to up the ante.

Rocket sled built by John Stapp which was code-named Sonic Wind No. 1 in the 1950s. Located at the New Mexico Museum of Space History. (Allens / Wikimedia Commons)

John Stapp becomes the fastest man on earth

On December 10, 1954, John Stapp would record his final run. This time, three additional rockets were added to the propulsion system in order to gain a massive 40,000 pounds of thrust. To minimise the risk of injury, Stapp’s arms and legs were strapped into the sled to ensure little to no movement. Additionally, he was asked to wear a helmet and hold a bite block in his mouth to protect his teeth. In a matter of a few seconds, the nine powerful rockets behind Stapp sprung into action. In about five seconds, the sled had reached a speed of about 630 miles per hour (1013.89 km/hr), or Mach 0.9. And just soon after, the brakes kicked in, and the sled was brought to a complete halt. The rapid deceleration translated to an unfathomable 40 plus Gs! Essentially, this meant that Stapp’s body weighed close to 6,800 pounds as it slammed forward when the sled stopped.

The damage to Stapp’s body was immense. All the blood vessels in his eyes had burst, rendering him momentarily blind. There were fears that he would never regain his eyesight. Additionally, he managed to crack a number of his ribs, while breaking both his wrists. The deceleration had also taken a massive toll on his respiratory and circulatory systems. But despite all that, he was in good spirits at the success of the test. Following the experiment, Time Magazine dubbed him, the “Fastest Man on Earth.”

All in all, John Stapp’s experiments were a huge success. They went on to prove that a pilot ejecting at high speeds and at an altitude of about 35,000 feet, could easily survive, withstanding about 45 G’s of force.

Footage of John Stapp experimenting on the effects of rapid acceleration and deceleration. (Youtube: PublicDomainFootage)

Enjoyed this article? Also, check out “Sergei Krikalev: The Time Travelling Cosmonaut“.

Recommended Read:

Sonic Wind: The Story of John Paul Stapp and How a Renegade Doctor Became the Fastest Man on Earth | By Craig Ryan

Recommended Watch:

Space Men – American Experience | PBS

Recommended Visit:

New Mexico Museum of Space History

Fact Analysis:

STSTW Media strives to deliver accurate information through careful research. However, things can go wrong. If you find the above article inaccurate or biased, please let us know at [email protected]