The Tragedy of Jallianwala Bagh

Share

A crowd gathered at Jallianwala Bagh during Motilal Nehru and Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya’s visit in the late summer of 1919. The meeting is taking place at the same spot as the platform was located on 13 April. (© Penguin Random House India)

The British ruled India for 89 years, from 1858 to 1947, and, while they did have their civilized moments, their rule was marked by wholesale pillage of the once vibrant Indian economy and a callous disregard for the lives of the people they had subjugated. Mr Wagner’s book focuses on an incident that stands out starkly for its sheer brutality in this dark period of Indian history – the massacre that took place in Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar, Punjab, on 13 April 1919.

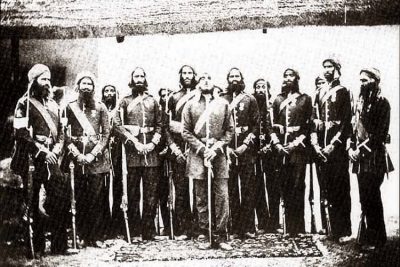

On Colonel Reginald Dyer’s orders, the troops from the 59th Sind Rifles, the 54th Sikhs, and the 2-9th Gurkhas entered through the main entrance of Jallianwala Bagh and, taking up position on a high earth bank, fired at point-blank range on their own countrymen. The people gathered in Jallianwala Bagh did not stand a chance, enclosed as they were in the walled Bagh and targeted with indiscriminate firing from guns with .303 ammunition.

“The wounds inflicted by the .303 ammunition had been devastating – at a distance of less than 600 feet, and what was at first practically point-blank range…”

The entrance to Jallianwala Bagh through which Dyer and his troops entered. The photograph shows the southern end of the Bagh, and the small shrine with its onion dome is visible on the left, while the part of the wall to the right is still to be seen at the memorial. Amritsar. (© Penguin Random House India)

The bullets ricocheted from the walls, pierced through people to hit the ones behind them, fragmented to injure all those close by, and even wounded and killed people living in the upper levels of the houses around the area. Many in the neighbourhood initially mistook the firing for fireworks. Of course, the pockmarks appearing on their houses soon wised them to the situation.

Locals inspecting bullet-holes in the southern wall, behind the shrine, in late 1919. This part of the wall no longer exists but would have been just to the left of the palm tree visible in other images. (© Penguin Random House India)

Nobody knows exactly how many people died on that horrendous day. The British afterwards gave out a rather low figure of 379 dead and 1,100 wounded, but the truth of the matter is they never bothered to make a serious count. According to eyewitnesses and the enquiry carried out by Madan Mohan Malviya and Motilal Nehru in the summer of 1919, the number was 1,000 dead and 1,500 wounded. In addition to those killed in the Bagh itself and its outskirts, many more succumbed later to their injuries, and many others suffered life-long from the injuries and the trauma of that day.

‘Jallianwala Bagh: An Empire of Fear and the Making of the Amritsar Massacre’ by Kim. A. Wagner, published by Penguin Random House India Private Limited, is concerned with the shooting and its aftermath, as recounted by those that lived through these events.

The Survivors of Jallianwala Bagh

When the troops finally withdrew from the Bagh, they left behind piles of dead bodies and scores that were dying or wounded. The dead included children as young as three. The Bagh was strewn with people’s belongings.

“After the soldiers had left, I looked round [. . .] There must have been more than a thousand corpses there. The whole place was strewn with them. At some places, 7 or 8 corpses were piled, one over another. In addition to the dead, there must have been about a thousand wounded persons lying there.”

It looked like a devastated battlefield, according to Lala Karam Chand, who survived by hiding in the Hansli drain.

Another survivor, Sardar Partap Singh, went to the drain to get water for a dying man and found dead bodies floating in the drain.

As dusk fell and the news of the shooting spread around the city, the local people hurried to Jalianwala Bagh to search for missing relatives and friends. It was a difficult, painful task that required them to turn over the dead and disturb the dying to find their loved ones. The bullet-ridden bodies had horrific injuries, with eyes and noses shot off, faces smashed, heads split open, chests and backs gaping open, and limbs blown off. It was here, in such a state, that Lala Gian Chand found his 17-year-old nephew Ram Labhaya.

Giridhari Lal, who went looking for his friend Hakim Singh and some young neighbourhood boys, recounted seeing an equally gruesome spectacle. To him, there appeared to be over 1000 dead bodies spread out around the Bagh.

It was getting close to the 8 p.m. curfew and people, afraid of being subjected to another shooting, began hurrying back to the relative safety of their homes. The dead and many of the wounded were left behind, and even though the people in the neighbourhood could hear the wounded moaning in agony and crying for water throughout the night, they didn’t dare to go out to help them.

“While the British authorities in Amritsar and Lahore had been busy throughout the night, the dead remained abandoned and exposed inside Jallianwala Bagh.”

Few of the shell-shocked people had the courage to ignore the curfew and one of them was Ratan Devi. She had spent the evening searching for her husband and it was dark by the time she finally found his body amongst a pile of other bodies. As all the other people in the Bagh had already left by then, she knocked on nearby doors and asked the people living there to help her move her husband’s body. When they all refused, she returned to the Bagh and spent the night at her dead husband’s side, weeping, chasing away dogs with a bamboo stick, and trying to comfort a dying 12-year-old boy.

A City in Mourning

“‘There was nobody present there, to register the number of the dead persons. Within one hour of our arrival in Durgiana, about 70 more dead bodies came for cremation, and others were following.’”

The following day, 14 April, was the day of the traditional Baisakhi Fair. A day to celebrate the harvest. Instead of celebrations, the people of Amritsar held cremations and burials. From dawn until dusk, at the Hindu Durgiana temple near the Lohgarh Gate and at the Muslim burial ground outside the Sultanwind Gate, the processions of the dead continued.

The north-eastern side of the Bagh, with the main entrance on the far left. The people in the photograph are standing on the earth bank from which Dyer’s troops fired. (© Penguin Random House India)

It will be 100 years this April since the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, but Mr Wagner’s matter-of-fact writing brings the deeply disturbing events alive as though it might have been yesterday. It is still difficult to make sense of the tragedy. While Rudyard Kipling did later claim that Colonel Reginald Dyer ‘did his duty as he saw it’, it seems a quite a worthless duty that calls upon anyone to murder their fellow human beings in cold blood and destroy so many scores of families.

For more details, read the book: