Bhopal Gas Tragedy: India’s Very Own Chernobyl That Affected Over Half a Million People

Share

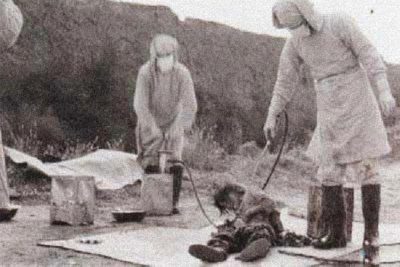

Survivors of Bhopal gas tragedy at Chingari Rehabilitation Centre. (Bhopal Medical Appeal / Flickr)

Why should modern technology go hand in hand with orthodoxy? Because we are too poor to afford a whole lot of automated systems. We have a huge number of unemployed people waiting to be given jobs. But, we must industrialize to become a ‘developed nation’. So we invite a multinational for a project. Pamper it in cocktail circuits. And when it gets going, we put a speed breaker. The multinational is forced to cut cost and go slow. The nose and the eyes of the labour, it is presumed, are enough to detect anything out-of-order. The whole system is forced into lethargy, and the way is crafted for the world’s biggest industrial disaster. That’s the story of the Bhopal gas tragedy that killed 3,500 people within days, but as many as 25,000 people have died from related illnesses and affected more than 500,000 people.

It began with inviting foreign direct investment

The intervening night of 2nd and 3rd December 1984 couldn’t have been more catastrophic. Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL) Bhopal, a subsidiary of Union Carbide Corporation (UCC) of America, released a huge amount of a toxic chemical in the air, accidentally. The chemical, methyl isocyanate (MIC), was stored in a tank in amounts exceeding the regulatory mandate. In the normal course, it would be used in the making of the product, an insecticide, called ‘Sevin’. Sevin was imported to India till the Indian government decided that it must be manufactured within the country. So, UCC was invited to establish a manufacturing unit for the Insecticide at Bhopal.

A sudden policy change was enforced

Accordingly, UCIL, the subsidiary of UCC in India since 1934, acquired land in Bhopal in 1969 for the manufacturing unit of ‘Sevin’. The American Company was directed to raise that at least one-fourth of the venture capital from local shareholders. The government itself had a 22% stake in the company’s subsidiary, Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL).

All was a honeymoon and hunky-dory between UCC and the Government of India till 1973, when a new act FERA [Foreign Exchange Regulation Act] was introduced, which required the dilution of foreign equity from 60 per cent to 40 per cent.

The UCC, which owned a 60 per cent stake in Union Carbide India decided that the company should reduce its investment to the Bhopal plant from $28 million to $20.6 million in order to retain control of its Indian subsidiary, and this meant poor safety standards. They also sought exemption from FERA by proposing to manufacture methyl-isocyanate (MIC) in Bhopal, which was later granted under “strict guidelines” in 1975.

The exterior of Union Carbide pesticide factory. (Bhopal Medical Appeal / Flickr)

Inside the Union Carbide pesticide factory. (Bhopal Medical Appeal / Flickr)

The decade of 1980 was tumultuous for India

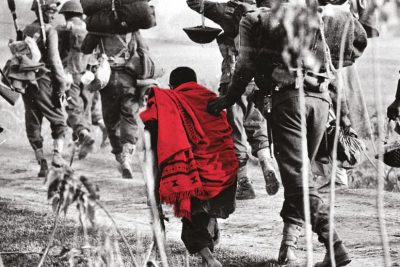

The first half of the 1980s was a politically volatile phase for India. The state of Punjab saw terrorism in the name of a separate homeland for Sikhs. Reign of Terror was part of Pakistan’s plan to cut off Punjab from India in the form of a new nation, Khalistan. The Indian government was forced to conduct Operation Blue Star to flush out terrorists from the golden temple in Amritsar. The hurt Sikh sought revenge by assassinating Mrs Indira Gandhi, the then Prime Minister of India, on the morning of 31st October 1984. This was followed by large scale pogrom that selectively killed Sikhs living in Delhi and other Indian cities. And that same year, on the intervening night of 2nd and 3rd December, the toxic gas MIC, leaked from the Bhopal plant, leaving a trail of death, and endless debate on ‘who was responsible’. Given the kind of political scenario prevailing at that point in time, sabotage wasn’t ruled out.

Count down began with indiscriminate cost-cutting

No doubt, someone in the Bhopal factory trespassed on duty. Someone was negligent. Otherwise, the lethal gas wouldn’t have leaked in such amounts as triggered death and incapacitation on a massive scale. But, first thing first. What really set the ball rolling? Doubtless, the cost-cutting exercise. There is a saying that you never know what enough is unless you have had more-than-enough. So, the innocuous and innocent-sounding cut-cost was the first step. It created a system which, over a period of time, became a harbinger of a lackadaisical production house.

Professionalism in the plant was reduced to a charade

As mentioned by The New York Times,

“The seeds of the accident were planted in 1972 when, under Government pressure to reduce imports and loss of foreign exchange, the company proposed to manufacture and store MIC at the plant”

Cost-cutting measures initiated in 1972 implied that technical staff, computers, and modern equipment must be reduced to a minimum. The lowering of standards led to increased employee turnover, and the number of rookie employees sitting on controls.

The workforce at the Bhopal plant had no expertise in sensing danger and tackling it timely. All they tried to do was to work in piecemeal and adhere to rule book as best as they could. In the process, they developed short cuts and go about their job mechanically, without foresight. What happened on 2nd December 1984 was a reflection of this attitude. Stored quantity of methyl isocyanate (MIC), a constituent of the finished product ‘Sevin’, rose to 63 tons. Of this lot, 42 tons were stored in tank number 601. That was full capacity fill even as the rule book said that the tank should never be filled more than half of its total capacity. The excess of MIC, as per the rule, should have been moved to a spare-tank. But, the spare-tank was full too. Workers had inadvertently got used to keeping even the spare tank full. That was a mistake. And there were many more mistakes. Like, all MIC was required to be cooled to a lower temperature. But the refrigerating unit was disbanded as part of the cost-cutting exercise. A scrubber cylinder meant for neutralizing toxic leaks, and a burner for the same purpose were dismantled for servicing.

High employee turnover affected the work culture

Workers on duty had reported leak at 11.30 PM on 2nd December. It was the toxic gas, MIC, starting to leak. In an hour’s time, the leakage became uncontrollable and people living in the vicinity began waking up due to lung distress, burning eyes and vomiting.

Control room safety board inside the abandoned Union Carbide factory. (Bhopal Medical Appeal / Flickr)

Investigations revealed that the Bhopal plant wasn’t able to sell all the Sevin it produced. It was sales deficit since 1982. Ensuing losses forced many highly trained professionals to quit the job and move to more prospective work areas. As plant lost money, management focussed on the economy to the serious detriment to safety norms. The leak, which was misconstrued as water-leak, was the doing of an untrained worker (less paid and hence fitting into cost-cutting exercise). The worker was directed by a trainee supervisor to wash an improperly sealed pipe, an act prohibited by the rule book. Through the defective seal, water seeped into the already overfull tank number 601. The stored MIC reacted with water raising internal pressure to a level where MIC broke through the tank cover. Of the three safety systems installed in the manufacturing unit, one had been taken off for servicing. The remaining two were unable to control the overwhelming leak.

Safety sign inside the now-abandoned factory. (Bhopal Medical Appeal / Flickr)

Even alarm systems were not distinctive

Shakil Qureshi, a MIC supervisor, revealed that the staff was used to defective and unreliable gadgets in the factory. Hence a gadget that worked well, got ignored too. He himself had noticed that pressure in one MIC tank shot up five times in an hour’s time. But didn’t realize it indicated danger. Tragically, the alarm that rang to alert for MIC leak went unnoticed. Reason being the sound of the alarm was no different from other alarms including one used for calling practice drill.

Prudence being the watchword in Bhopal plant, computer systems which could monitor operations, and sound timely warning to attending staff were not installed. Workers can sense irritating leaks using their sense of sight and smell, thought the Indian management. But the UCC manual clearly said, ‘Although the tear gas effect of the vapour is extremely unpleasant, this property cannot be used as a means to alert personnel.’ Budget restrictions reflected on the training of the manpower too. Employees knew they worked in an unsafe environment. In 1983, the number of operators in a shift was reduced from 12 to 6. Kamal K. Pareek, a chemical engineer had remarked in 1971: “(the plant) cannot be run safely with 6 people”. No public relations exercise was ever done to familiarize the city of Bhopal with what the factory was doing. And what possible dangers it posed to life and the environment around it.

Gas-leak created all-around panic

The circumstances were favourable for a tragedy of epic proportions. Panic was naturally the first reaction of workers in attendance at the pesticide factory. There were buses in plant premises which could have ferried them quick and far. But fear was so overwhelming that the vehicles were ignored. Poignantly though, as it emerged later, even running helter-skelter didn’t help. People who stayed put in their home, willingly or helplessly, survived. And those who ran out met toxic clouds on way and died a painful death.

Approximately 40 tonnes of methyl isocyanate, along with other toxic chemicals, got released from the Bhopal factory. The toxic MIC floated at random, killing people in running trains, on roads and wheresoever it could dip or rise with the free-flowing air. Slums and villages near the factory were worst hit. Half of the 8.5 lakh population of Bhopal city coughed, suffered difficult breathing, and itch in eyes and skin. Internal haemorrhages, pneumonia and respiratory failure caused deaths on a large scale.

Doctors panicked

No public alarm was raised by the UCIL. The fatal hit of floating MIC clouds caused mayhem, and people rushed to hospitals in large numbers. Government hospitals, only 2 in number then, neither had the capacity nor the expertise to treat such large number of toxic gas patients. Confusion in the medical circle was so paramount that even routine drug, sodium thiosulphate, wasn’t used in the period it was critically required. Instead, doors of UCC were beaten for medical guidance. A formal guidance was provided, but that was inadequate. The government claimed that the leakage of MIC was stopped in 8 hours. But the effect and after-effects of gas leak remain even to this day, i.e. 35 years after the incident happened. The overall tally of the dead is over 25,000 people. Thousands got deformed as the toxic effect was genetically transmitted to the next generation. Even now, the newborn show tell-tale symptoms of physical and mental deformity.

Birth defects are still reported children in the region. (Bhopal Medical Appeal / Flickr)

Let us look hard on our own selves

Now, let’s separate the grain from the chaff. UCC America and the state of India were pitted against each other in a legal battle. Naturally, both accused each other for the Bhopal tragedy. Warren Anderson voiced sabotage theory which was rebutted by the Indian side. A detailed investigation led to the conviction of some employees in the chain of command and they were punished as per the Indian laws. Compensation, as decided between American and Indian courts, was doled out to victims. Many NGOs worked, and are still working for the rights of the gas affected. And there is a feeling in the Indian camp that justice was delayed, and dispensed in favour of America. But, let us rewind and begin from the very start. UCC was given business opportunity in Bhopal purely on merit as it was already operating in India as Union Carbide India Limited since 1934. The product it was called upon to make-in-India, Sevin, already had a market. Those were the days when the green revolution was at peak and pesticide were deemed indispensable for agricultural crops. And, just when UCC was all geared up to deliver a classy industrial unit, the Indian side said: gear down. We don’t want machines that would make human labour redundant. We have an acute shortage of jobs. We want the Bhopal factory to be a job provider for the local population. And UCC was forced to step back and cut costs ear-marked for computer technology which alone could have ensured safety to the Bhopal plant. Political compulsions of the day came in way of the state of art industrial technology. And, the Bhopal plant became a cross between technique and tradition.

Union Carbide pesticide plant today in Bhopal, India. (Julian Nyča / Wikimedia Commons)

India’s disaster management record is poor

If past is any guide, disaster management or crisis management in India leaves much to be desired. Rhetoric overtakes logical investigation. Political posturing comes into the forefront. If the diagnosis and treatment of the patients remained in suspense for long, we can’t blame America for it. It was natural for India to bay for Anderson’s blood. But let’s not forget, he wasn’t responsible for the cost-cutting drive, nor for the loss of market for Sevin. And let’s not forget that the only consistent finding, the only undisputed finding, in the entire trail of investigation is mismanagement. The emotional quotient of the tragedy shouldn’t blind us to the fact that it was our own policy-making which paved way for a tragedy of this magnitude. Chaos and mayhem that followed the gas leak, didn’t permit a fair and time-bound investigation. In fact, sabotage under those conditions could have very well happened, without leaving any trace for the investigation agencies.

Bhopal gas tragedy memorial statue. (Bhopal Medical Appeal / Flickr)

The Indian and the American judiciary worked in top gear

Judiciary in India, as well as America, have done their part on the issue. UCC paid a compensation of $470 million for the victims in 1989. Politicking on the issue made waves even in 2019 general elections. In the 35 years past this tragedy, political parties have blamed one another for the disaster and siding with the American company. The CEO of Union Carbide and the chairman of UCC, Warren Anderson, was seen as the main villain behind the gas disaster. He died on Sept 29th 2014, without being deported to India to face trial. Many believe he escaped punishment for two reasons. One, protection by the US government. Two, negligence of the Indian government.

Author’s Opinion

So the takeaway from Bhopal disaster is that let’s clean our own house first. Let’s not compromise with professional expertise. Giving jobs to untrained and unqualified people is no way to remove unemployment, or save a business from loss. Politicians shouldn’t play to the gallery in matters of hardcore business. This is the only way out to prevent tragedies, like the Bhopal gas-leak, in future.

You can make a donation to the Bhopal Medical Appeal and help fund the important work taking place at Chingari: bhopal.org/donate/

Also, check out “The Bengal Famine of 1943: The Man-Made Famine That Killed Around 3 Million Indians“.

Fact Analysis:

STSTW Media strives to deliver accurate information through careful research. However, things can go wrong. If you find the above article inaccurate or biased, please let us know at [email protected]