Battle of Los Angeles: When the City Fought a Bizarre Battle with Nobody

Share

Battle of Los Angeles: Searchlights directed towards an unidentified object seen in the sky on 24 February 1942. (Los Angeles Times / Wikimedia Commons)

In true Hollywood style, Los Angeles once fought a battle that never was. It is a well-known fact that the participation of the United States in World War II was instigated by the Japanese. The Imperial Japanese launched a surprise attack against the United States, on Pearl Harbour in Hawaii in the early morning hours of December 7, 1941. What followed then is history. It saw the involvement of the United States in World War II as one of the formidable Allied forces.

The events that led to the battle of Los Angeles

Needless to say, after the military strike on Pearl Harbour, the Americans were wary of an impending enemy attack. The hyperactive nervous tension amongst the armed forces was causing a frenzy at the slightest hint of an attack.

December 9, 1941, set invasion tremors in New York following a misleading, unconfirmed information of an approaching aircraft. Moreover, there were reports from the West Coast of the country of suspicious overactive young pilots and radar men mistaking anything in the waters for an enemy attack.

Apparently, they were mistrustful of everything they saw; fishing boats, floating logs, and sometimes even whales were erroneously assumed to be Japanese submarines.

An increase in Japanese activity off the West Coast had added to the public’s fears and confirmed the reality of the Japanese threat. By December 17 in 1941, the Japanese Sixth Fleet had nine submarines stationed near the West Coast.

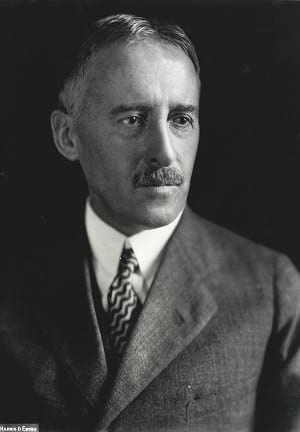

Henry Lewis Stimson. (Harris & Ewing / LOC)

In addition, an announcement by the U.S. Secretary of War, Henry Lewis Stimson, made matters even worse. Germans had attacked the island of Aruba on February 16, 1942, causing damage to the oil refineries and disrupting the fuel supply to the Allied forces. A few days later, on February 19, Stimson announced that the public should be prepared for “occasional blows” since the Army could not be dispersed everywhere.

One of the submarines, the 1-17 surfaced at Goleta, near Santa Barbara in California February 23rd 1942, and fired 13 rounds into the Ellwood Oil Field. Fortunately, it was unable to inflict severe damage. Even though the attack did not cause any casualties, it marked the first bombing of mainland United States. The defence mechanism of the country was having an overload of attack jitters.

Los Angeles air raid

On February 24, 1942, the US Naval intelligence issued the warning of a probable attack within the next 10 hours. That same evening, following reports of flares and blinking lights in the sky, an alert was sounded at 7.18 pm via air raid sirens.

However, the alert was lifted at 10.23 pm when nothing untowardly could be detected during that time period. The defence forces, on the other hand, continued a vigilant lookout for enemy attacks. A few hours later, in the early morning hours of February 25 at around 2.15 am, the radars picked up an object flying 190 km off the coast of Los Angeles.

A realisation dawned on the American soldiers that a war was imminent. Troops were put on “Green Alert“, in a ready to fire position and the searchlights lit up the sky. By 2.21 am it was confirmed that the object was closing in on the city and a city blackout was initiated to prevent identification of targets by the enemy.

Reports of enemy planes over the city started pouring in, though the object approaching seemed to have dropped off the radars and vanished. A 78th Coast Artillery Regiment located in Long Beach reported of enemy planes over the Douglas Aircraft plant. A coast artillery colonel saw 25 planes flying at 12,000 feet towards Los Angeles.

Just a little after 3 am, antiaircraft guns started firing at an object seen above Santa Monica and the Battle of Los Angeles began, continuing over the next 1 hour. Whatever it was that was spotted in the sky, it showed no signs of attacking and neither was it destroyed. The gunners fired 1,440 three-inch shells of antiaircraft guns into the sky without any sign of enemy aircraft fragments or any other enemy damage. By 4 am, it was obvious that there was no enemy threat but the alert was only lifted by 7.21 am.

During the firing, as the shells lit up the sky above the city with explosions, the raining shrapnel caused damage to homes and other building structures. The residents of the city watched the unfolding drama standing on rooftops and hills along the 40-mile arc of the coastline. There were few civilian casualties reported due to the shrapnel and unexploded ammunition that fell. A couple of people were reported to have died of a heart attack due to the tension of an invasion. After the “all clear” was issued; various theories, speculations and explanations followed.

Investigations & aftermath

The official reports that came in from the various regiments stationed along the coast confirmed that enemy planes were definitely flying over the city between 3 am and 4 am. The commanding general of the Southern California Sector in Fort MacArthur stated in his report that a detachment in Santa Fe had sighted 14 planes flying south at 2.35 am. He went on to confirm this by corroborating information received at 3.28 am from Artesia that 14 or 15 planes had been spotted flying west. His report concluded that the presence of unknown planes over Los Angeles from 2.30 am to 4.30 am had been established.

After receiving all the reports and compiling the information, the Army authorities decided on an official count of 15 enemy planes over Los Angeles. California congressman William Johnson made an official statement of 15 planes sighted “flying at slow speed from 9,000 to 18,000 feet“. Later that day the Secretary of War, Henry Lewis Stimson also issued a statement confirming 15 planes, though he made sure that his statement was ambiguous enough to get out of. He mentioned that the planes might have been enemy operated commercial flights flown in numbers to terrorise the Americans or to detect strategic antiaircraft units.

Soon afterwards, the Naval Secretary William Franklin “Frank” Knox announced at a press conference that the air raid had been a false alarm and probably the result of “jittery nerves“. The Air Force and the Navy confirmed that there was no conclusive proof of enemy planes flying over the city on February 25, 1949. The fact that no aircraft carrier could be located in the vicinity dismissed the possibility of an aerial attack. After World War II ended, the Japanese confirmed that they had not partaken any such activity on that fateful day.

Eventually, news started trickling in that the panicking soldiers could have been firing at a floating meteorological balloon. Balloons of 4 feet in diameter were often released by the regiments stationed around Los Angeles.

Weather balloon being prepared for launch. (NOAA Photo Library)

This was to stay updated with the wind directions to make necessary changes in firing of the antiaircraft guns, accordingly. Two regiments had released meteorological balloons in that time frame, that had been carried along the coast with the wind. The balloons were tied to a glass ball with a candle inside to enable tracking at night. However absurd or hilarious the accounts of that day maybe, they do not take away from the dreadful threat of an enemy attack.

Enjoyed this article? Also, check out “Area 51: Is America Really Building UFO’s?“.

Fact Analysis:

STSTW Media strives to deliver accurate information through careful research. However, things can go wrong. If you find the above article inaccurate or biased, please let us know at [email protected]