A Peek Into The Dark Times That Befell Assam and Its Effect on the Modern-Day State

Share

Assam- The Accord, The Discord. (© Penguin Random House India)

Assam-born Sangeeta Barooah Pisharoty became the first ever female journalist from the Northeast to work on the forefront in covering news from the North-eastern states. Having won several awards for her in-depth reportage over the years on matters related to the states, Sangeeta Barooah Pisharoty turned her attention to penning a book. Assam – The Accord, The Discord is a first-hand account of her own experiences and memories of the signing of the Assam Accord of 1985, which as per her narration, came with its own fair share of negatives.

In her debut book, she mentions how the signing of the Assam Accord left the state in terrible times. The insurgency was at its peak, streets witnessed bloody wars, the political scenario was in disarray. And common people had no choice but to flee Assam in search of a better future. In conversation with Biraj Sarma, one of the key players of the Assam Accord, the author gives a detailed account of the past – the signing of the Memorandum of Settlement (MoS) and how it affected the present – updating of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) and the controversial amendment to the Citizenship Amendment Act.

The Beginning

In the year 1985, when the author was in school, the Punjab Accord had just been signed in July. It was only a matter of time before Assam got its share of the limelight, for which student bodies and local parishads were quite stirred up in the state. Although none knew what the Accord would entail or how it would assure the Assamese regarding preservation and protection of their culture and identity.

When the author met Biraj Sarma, one of the three key signatories of the Assam Accord of August 1985, she realized all the efforts of the students’ agitation – the Assam Movement – were not very easy to come by.

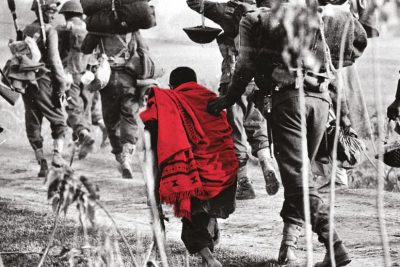

Students rally during the Assam Movement, 1985. (Wikimedia Commons)

A picture on the wall of Sarma’s home, which has now come to be associated with the signing of the MoS, took both the author and Biraj Sarma back in time.

While the then Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi looked excitedly at the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU) general secretary, receiving the signed copy of the Accord from the Union Home Secretary, members of the All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP), seemingly looked confounded.

Special Indian Air Force planes had picked up members of the AASU and AAGSP from Guwahati a few hours before the Accord was to be signed. Another IAF flight brought in executive members of the student body late in the evening of August 14, 1985.

“On 13 August, all the executive members of AASU and AAGSP were hurriedly summoned to Delhi by the Union home ministry to hold ‘a detailed and broad based discussion on the Assam problem.”

The Disagreement

After the Accord was signed and the signatories returned to the guest house with the final draft, not everything went well between the AASU and AAGSP members. Some disagreed with a particular clause mentioned in the draft. The clause read, in an exclusive provision for the state, it would segregate foreign nationals from Indians living in Assam before March 24, 1971. Although their original demand was 1951, as per the NRC that would determine who the citizens of Assam actually were. Heated argument also ensued amongst the group regarding no clear promise from the central government on scrapping of the Illegal Migrants (Determination Tribunal) (IMDT) Act. However, key AASU members made sure there was no more scope for negotiation.

“[Union home secretary] R.D. Pradhan told us that the government couldn’t scrap an Act passed by Parliament just like that, but it will try to create a political consensus for its removal…”

While deliberations went on and some of the members opposed the final draft. It was said that the central government had agreed to provide an Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) in Guwahati, along with a central university.

“Did we agitate for six years for an IIT and a central university?”

Much later, amidst games of hide and seek, the group went to the Prime Minister’s residence settling for the fact that it was the best possible deal and that there was no more time to waste on this matter.

“…Officials, ‘kept putting pressure’ on them throughout the day on 14 August to somehow arrive at an agreement since Prime Minister Gandhi had decided to announce the Accord in his Independence Day speech at the Red Fort the next morning.”

A Dent in the State

After the Assam Accord was signed and PM addressed the nation the next day, the Assamese felt liberated as the old dream of autonomy and civil liberties over their homeland was achieved. But while many cheered the decision, minority groups rose up in shock and anger.

“…What particularly infuriated them was the Centre’s approval of 1966 as the base year for citizenship enumeration in the state. As per Clause 5 (2) of the Accord, the names of those foreigners who entered Assam after 1 January 1966 and up to 24 March 1971, ‘shall be deleted in accordance with the provisions of the Foreigners’ Act, 1946…”

Seed of Dissent

As minority groups kept protesting, AASU demanded the revaluation of the electoral rolls, which had names of thousands of foreign nationals (of Bangladeshi origin), that they originally wanted to weed out in their demand for revision before the General Elections of 1980. In one of his speeches, the then Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) S. L. Shakhder mentioned how foreign nationals were largely and improperly included in the electoral rolls, particularly in the North East, thereby enraging the people.

“…People of East Bengal lineage – both Hindu and Muslim –they intended to make Assam a part of their extended Bengali homeland by negating local language and culture…”

Another reason for Assam‘s rage was that, while the hill tribes of other north-eastern states were protected under the Constitution, the people of Assam were overlooked. Also, the non-Congress leaders were under the impression—Congress took calculated risks to have a voter base constituting illegal immigrants from the other side of Assam’s border. This led to further issues in the state and discord crept up in the parties.

As the book progresses further, the author narrates Prafulla Kumar Mahanta ‘s journey to becoming the youngest and the most controversial Chief Minister of Assam and how his two tenures resulted in some of the toughest times in the state. Assam – The Accord, The Discord also looks at the six-year-long agitation against illegal immigrants that gave rise to the recent uproar on the NRC in Assam, the essence of which was the deportation of people, who failed to prove their Indian citizenship.

Sangeeta Barooah Pisharoty’s book is a detailed account of what made Assam the state it is today and is a perfect page-turner.

More about the book:

Assam- The Accord, The Discord | By Sangeeta Barooah Pisharoty

Assam- The Accord, The Discord | By Sangeeta Barooah Pisharoty