The Turk: 18th Century Automaton Chess Player was a Forerunner of Computer Age

Share

The Mechanical Turk and its inner working. (© Jan Braun / Heinz Nixdorf MuseumsForum / Used With Permission)

Man’s fascination for machines and gizmos predates industrial revolution when machines were replacing manual labour, draught power, and even entertainment in a big way. Then a path-breaking feat happened in the 18th century. A machine arrived on the scene not to replace horsepower, but cerebral power. It was a replacement for man’s ability to think critically. A machine could play chess against a man, and more often than not, beating him in the game.

The machine, the Turk was a mannequin of a sorcerer like, a wide-eyed, turbaned and moustachioed man sitting behind three and a half feet long, two feet wide and two and a half feet high wooden cabinet studded with Chess Board. Automaton Chess Player or the Robotic Chess Player were other names for The Turk. The machine was conceived, created and designed by Viennese Engineer Wolfgang von Kempelen in 1770.

Projected as chess playing contraption, the machine remained in vogue, though intermittently, for 84 years, giving tough time to whosoever sat on the rival’s seat. It defeated best of chess masters and became a rage. How the machine really worked, would take time to become public. In those days of the industrial revolution, machines of all shades and description evoked immense awe and surprise for their physical output. And here was one doing mental work of tall order. People hooked to magic shows for entertainment in those days couldn’t have asked for more.

The reconstructed version of The Turk at the Heinz Nixdorf Museum, Germany. (Marcin Wichary / Flickr)

Theories about the working of the Automaton Chess Player

The inaugural show of the Robotic Chess Player was held in Habsburg court in Vienna. Maria Theresa, the Queen of Hungary and Bohemia, was deeply impressed. After the inaugural show, the Turk went into a hiatus till after Maria’s death, her son Joseph II would revive it. In a 1783 Paris show, Benjamin Franklin played with the machine and lost.

In the following years, it toured England and Germany and came on the radar of sceptics. People started doubting the Turk. British author Philip Thicknesse said an automation couldn’t be passed as a chess player. He rejected the possibility of chessboard being manipulated from distance, magnetically or otherwise, as many believed. However, he proposed that the cabinet concealed a child of 10, 12 or 14 years, who was exceptionally talented in the game of chess.

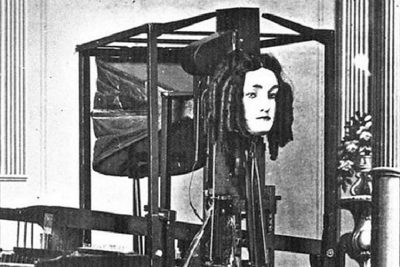

The Turk. (Carafe / Wikimedia Commons)

Just as a magician shows his empty hands to crowds before performing tricks, Von Kemplen showed innards of the cabinet, revealing largely empty space, and an ensemble of cogwheels as if those were the brain of the Robot machine. Hand movement of Turk was precise, man-like, in placing chess pieces on board. The other player was chosen from the crowd.

Compared to the-then prevalent shows of animal and human dummies, the Turk provided a far superior option for mass entertainment. It was a dummy not only moving head and hands but also expressing anxiety and indignation like Chess wizard. When Napoleon Bonaparte, the iconic opponent of Turk, tried to cheat, the angered Robot uprooted all chess pieces, amusing Napoleon to no end.

So how did the Mechanical Turk work?

The maverick machine had to put up with some-one-is-hiding-inside-the-cabinet theory for decades. The cabinet was big enough to house an individual, child or an adult, who could execute chess moves directly or by some kind of remote control. The concealed person hid in the bottom drawer as the cabinet was opened for the perusal of the audience in candlelight. The hidden person being a fugitive amputee and good-at-chess Polish soldier, Worousky, who Von Kempelen met in Russia, was also mooted.

Illustration from a book trying to explain the workings of the Mechanical Turk. (Joseph Racknitz / Wikimedia Commons)

Hearsays and rumours added to the mystique of the Chess machine but the truth was plain and simple. There indeed was a skilled operator inside the cabinet, trained and groomed for the game.

The mystique of the chess playing Turk grew by the day. Robert Willis, English Academic and Mechanical Engineer, 1821, wondered what more could these humanoid machines accomplish in times to come. Charles Babbage, the English Polymath, was so impressed he got down to work for a machine which could automatically calculate and tabulate mathematical functions, a harbinger of present-day Artificial Intelligence. Tom Standage wrote “…… (A machine like Turk) raised the possibility that machines might eventually be capable of replacing mental activity too.”

What made The Turk so impressive?

The explanation lies in the surprise element which it was able to generate. The game began with the mannequin moving head sideways to survey the chessboard. The grim expression on the wooden face, moving eyes, the gentle tapping on board in a manner of brainstorming, moustaches and headgear of an oriental magician; all these combined to overawe, if not unnerve, the rival player. And then there were instances when machine threw tantrums over perceived cheating by the opponent.

With the death of Kampelene in 1804, Turk came in the custody of Bavarian showman Johann Nepomuk Maelzel who organized shows in the USA in the 1820s and 30s. In 1830s Maelzel, as well as the hidden operator of Turk, died of yellow fever in Cuba.

Noted American writer Edgar Allan Poe, published an essay in 1836 to prove that Turk was assisted by a hidden human. By 1850, hysteria generated by Turk was on the wane. Left as antique in a Chinese museum in Philadelphia, it was destroyed in a fire breakout in 1854. The final nail in the coffin of The Turk came from Dr. Silas Mitchell in 1860. He elaborately revealed secrets of the Automaton Chess Machine in his magazine named ‘Chess Monthly’.

Yet, it would be an understatement to call Turk just a hoax or a clever deceit. The frenzy that it generated in heydays impacted laymen and elite alike. Father of the present day Computer, Charles Baggage, was defeated twice by the automaton. The machine and magic combo – Turk verily foreshadowed Artificial Intelligence of today. And that’s no ordinary gift of the Turk to the posterity.

Enjoyed this article? Also, check out “Euphonia: The Sad Story of Joseph Faber and His Creepy Machine That Made Ghostly Sounds“.

Recommended Visit:

Heinz Nixdorf Museum | Paderborn, Germany

Fact Analysis:

STSTW Media strives to deliver accurate information through careful research. However, things can go wrong. If you find the above article inaccurate or biased, please let us know at [email protected]